Eliminating Infectious Diseases

For Dorothy J. Wiley and Dong Sung An, it was the rise of the then-mysterious disease called AIDS in the early 1980s that set them on their current research paths. For Wei-Ti Chen, it was her work in the 1990s as a nurse-midwife taking care of patients infected with HIV.

Now these three members of the UCLA School of Nursing faculty are at the forefront of research in their specialities, aiming to make a difference for those infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and, in Wiley’s case, human papillomavirus (HPV).

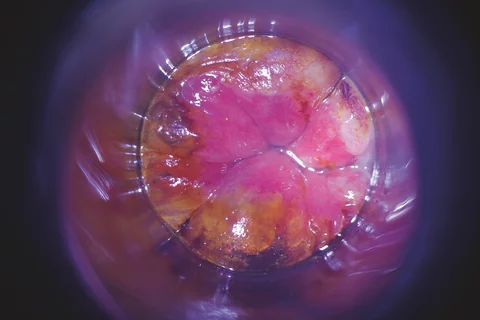

Professor Wiley, PhD, RN, FAAN, has focused on community and public health prevention strategies for both HIV and HPV and on finding ways to help better fight HPV infections. Improved screening methods for cancers caused by these viruses, early diagnosis and precancer treatment and methods that improve patient adherence are all areas of focus for Wiley. Thirty percent of cancers are caused by external factors, such as viral infections like HPV.

The American public is becoming increasingly aware that HPV can cause cervical cancer in women, but it also can cause anal and oropharyngeal cancer in both women and men. A 2013 study led by Wiley found that HIV-positive men who have sex with men are at higher risk for the type of HPVs that most often cause anal cancer. A 2017 study published in Lancet and co-authored by Wiley, looked at various factors of an HPV vaccine that prevented infection by 9 different HPVs administered to women ages 16 to 26. Researchers found the 9vHPV vaccine prevented infection, cytological abnormalities and precancerous lesions. These studies are in their early stages and will follow many vaccinated women across the lifespan. Already protection lasts for six years and “could potentially prevent 90 percent of cervical cases worldwide for a lifetime.”

“We have the ability to stop cervical cancer dead in its tracks, oropharyngeal and anal cancers too, if we do nothing more than get people vaccinated,” Wiley said. “It saddens me daily that somebody dies from HPV-cancers in a country where screening and an effective vaccine are both available."

Wiley noted that in countries where people don’t have access to screening prevention services, there are about 500,000 new cases of cervical cancer per year and about half the stricken women die. In the United States, with all the screening and treatment that is available, nearly 12,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2017 and nearly 4,000 died. With screening, the number of new cases of cervical cancer has dropped about 70 percent.

With the advent of the HPV vaccine for young adolescents, “we really have the ability right now” to end HPV-caused cancers. We can prevent nearly 90 percent of cervical cancers in our daughters’ and grandchildren’s generations, and as many anal cancers in this next generation and beyond, Wiley said.

Having an effective vaccine is exciting, Wiley said, “but it’s also depressing that only about one third of these young adolescents are being vaccinated. We have to find better ways to strategize to get people to become vaccinated and among those in my generation and yours, to seek diagnosis and treatment.”

Professor Dong Sung An, MD, PhD, was a medical student in Japan when AIDS erupted in the international consciousness. “I learned there were no drugs or therapy for AIDS back then and I wanted to find a therapy for an HIV cure,” An recalled. After medical school, he went to a graduate school for HIV/AIDS research.

Since 2016, the prognosis of HIV infection has been dramatically changed by the implementation of highly active antiretroviral drugs. It has dramatically reduced the number of AIDS deaths. However, the drug therapy cannot provide an HIV cure.

An said the only human being ever cured from HIV/AIDS was Timothy Ray Brown, “the Berlin Patient,” through a bone marrow transplant from a rare naturally HIV resistant donor. Approximately, one percent of the world’s Caucasian population are naturally immune to HIV due to a variation in their CCR5 gene. CCR5 is a receptor (like a docking station) for HIV to attach on a cell surface and to initiate infection. For people who carry the gene variation of CCR5, the virus cannot take hold. After transplanting the rare natural HIV resistant bone marrow, Timothy Ray Brown’s immune system was successfully replaced with HIV resistant cells and HIV has become undetectable since then. However, due to the difficulty of finding HIV resistant tissue type matched donors, a second case of an HIV cure has not been reported.

An’s team is working on genetic engineering of patient blood stem cells to create that CCR5 gene variation using RNA interference and more recently CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing techniques funded by NIH. His RNA interference technology to reduce CCR5 expression has been studied for the feasibility and safety of the experimental CCR5 gene modification in patient blood stem cells in a phase I/ll clinical trial. A recent paper on one of his studies, published in Molecular Therapy Methods & Clinical Development by the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy, involved testing a new form of gene therapy on humanized mice that had previously been infected with HIV. The goal is to develop a way to treat humans infected with HIV.

At UCLA since 1995, An said he is pleased to be at such a pioneering research institution. He noted it was UCLA researchers who first identified the virus that causes AIDS in humans.

“UCLA has a very highly enriched AIDS and HIV research program. The support from the UCLA School of Nursing allows my research team to pursue our research to cure HIV/AIDS.” An said.

Associate Professor Wei-Ti Chen, RN, CNM, PhD, FAAN, is specializing in issues related to women and children with HIV/AIDS in China and in immigrant health issues focusing on Asian immigrants.

Chen, who joined the School of Nursing faculty this year, is working on a project to find effective self-and family-management interventions for Asians living in New York.

“Many of these [people living with HIV/AIDS] are facing difficulties regarding stigma, disclosure, symptoms management and family support,” Chen said.

One of the most rewarding things about her work is being “one of the first professional providers to talk [to patients] in greater detail regarding their experiences with HIV,” Chen said.

“To get those diagnosed with the disease to open up is difficult enough, but to get them to discuss greater details with professionals is almost impossible,” Chen said. She said her cultural connections are especially helpful. She is also pleased that her projects in China enable her to share interventions that have been tested in other countries and that can be adapted to China’s collective culture. Among Chen’s recent published work is a study of how people with HIV/AIDS in China withdraw from societal contact.

“I am glad that I can serve as one of the most important connections to show the mainstream public that HIV positive Asians exist and they are suffering as HIV positive individuals in this country are.”

— by Jean Merl (a retired LA Times reporter and a proud Bruin MA ’72)